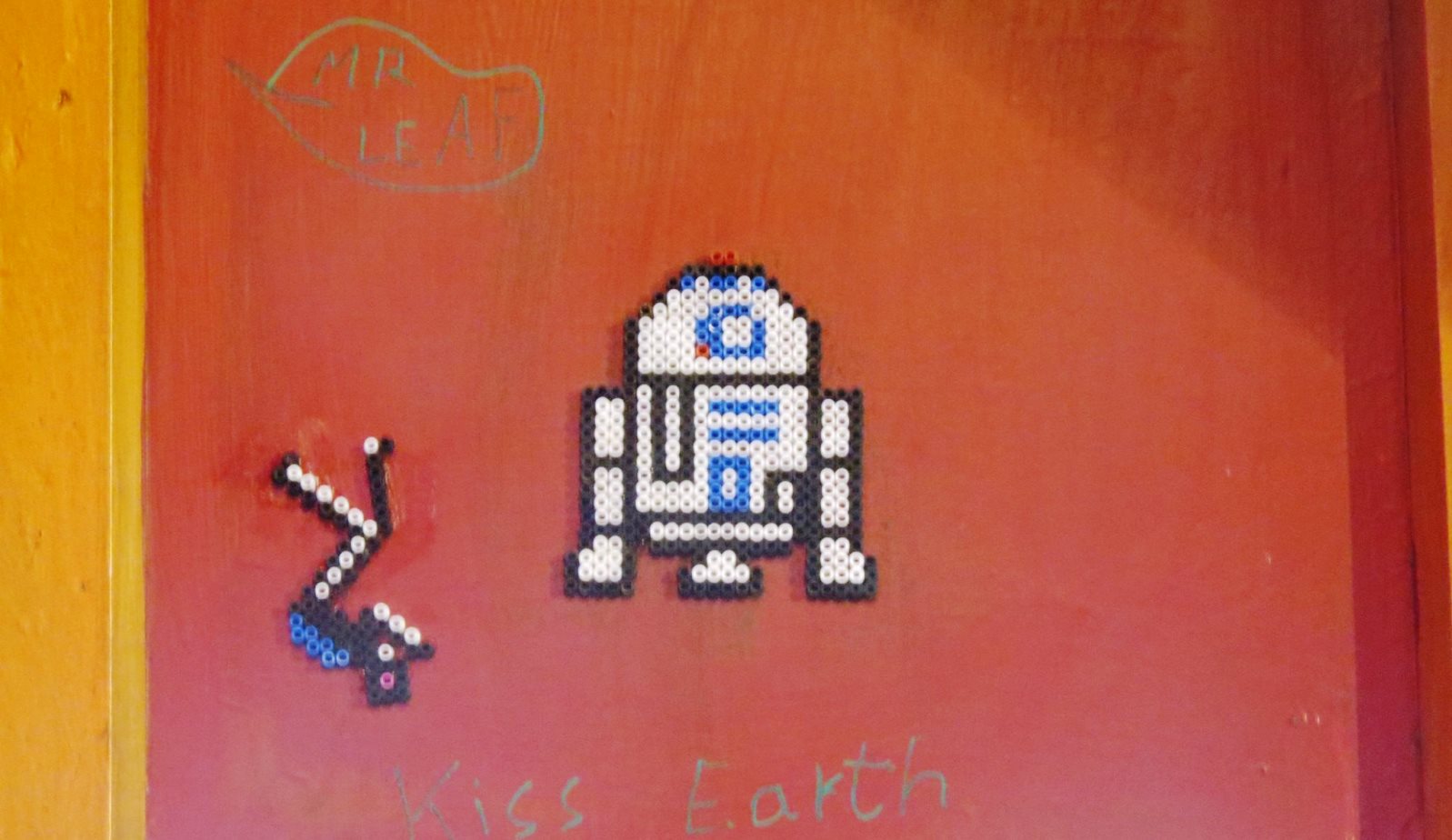

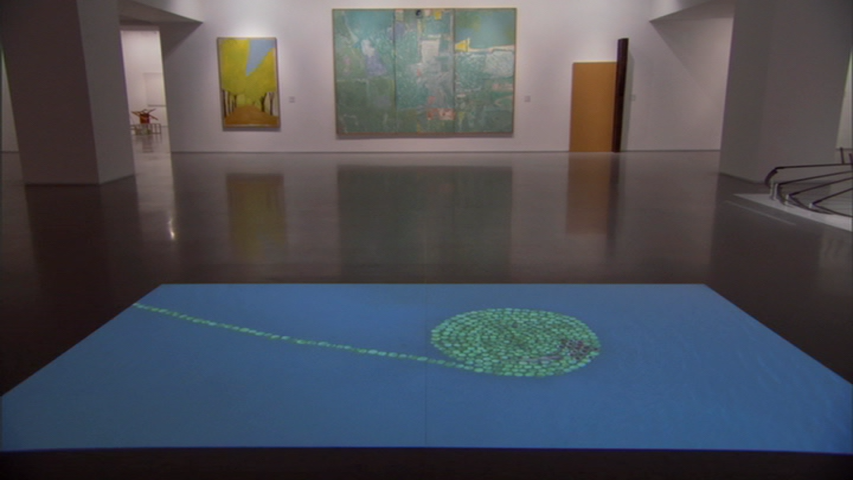

Orit Wolf performing in Ashdod. Photo by D. Miller

Award-winning Israeli musician Orit Wolf believes that to survive in the 21st century business world, ‘you have to be amazing, just like a performer.’

Israeli concert pianist Orit Wolf was barely out of her teens when disaster struck 12 minutes into a live recording and concert in Jerusalem: She blanked out and froze.

“I was always told ‘the show must go on’ but nobody told me how to do that, how to turn a mistake into an opportunity and how to improvise. I stopped the music and it was such a shameful occasion,” recalls Wolf.

Today, the poised pianist performs across the world and leads internationally sought-after workshops using music to teach businesses innovation, problem-solving, management, public speaking, coping with change, the power of persuasion and the art of disruption.

“I realized that if I want to be on stage I’ve got to have the right tools to turn any mistake into something beautiful. So I started to learn composition and improvisation and it was like buying an insurance policy that no matter what happens I can go on and do a lovely performance even if I don’t have my notes or forgot the music or the piano is really bad, or my hands are sweaty or the audience is noisy,” she tells ISRAEL21c.

Her research following that ruined concert convinced her that “there was something in music-making that could give insights to so many professions on how to go on no matter what happens.”

Wolf was only 23 when an executive from Israeli pharma giant Teva audited one of her classes at Tel Aviv University about music and innovation, and persuaded her to start lecturing to businesses.

Over the past decade, she’s worked with banks, insurance companies, colleges and firms such as Verint, Matrix, Check Point, Strauss, Coca-Cola, HP, IBM, Bayer, Lilly, FedEx and Netafim. Her concert lectures have taken her to countries including Holland, Switzerland, England, Germany, Spain and Austria. This fall she’s returned to her alma mater, the Royal Academy of Music in London, to teach a course called “Leadership for Stage Performers.”

Below is a presentation Wolf gave at the UK Marketing Society’s 2014 annual conference.

“I don’t teach strategies you can read in a book,” Wolf says. “I give tools to create disruptions, to improvise and deliver your message in a more experienced and inspiring way. To survive in the 21st century you have to be amazing, just like a performer. It’s easy to show on the piano how you can take the same text or score and transform it.”

In one exercise, Wolf asks participants to write on paper for three minutes and to make intentional spelling mistakes. She then analyzes results in a 45-minute presentation.

“What we learn is that the average person makes 20 mistakes in 40 words. People who make more mistakes than words, say 20 words with 40 mistakes, are less afraid to break paradigms. And what kind of mistakes they make shows different ways of breaking the paradigm. It’s very interesting for me to see how far people are allowing themselves to go.”

Another exercise has the group telling an improvised story passed from one to the next, in which every other word must be spoken in a different language. For example, instead of “good morning” you might say “good boker.”

“I have about 80 different exercises like those to break your paradigms on emotional, mental and cognitive levels. We create a situation where you will not be afraid to be cognitively embarrassed. This trains you to have the courage and self-confidence to deliver your next presentation beautifully even if you have technical problems.”

Born leader

Orit Wolf persuaded her parents to send her for piano lessons when she was six. Gifted in many areas, she finished high school at 16 and by age 23 had acquired a bachelor’s degree from Boston University on full scholarship, a master’s degree from the Royal Academy of Music and a PhD from Bar-Ilan University, along with numerous piano awards.

She then taught innovation through music at Tel Aviv University for eight years despite never having studied leadership, marketing or business management.

“I’m dedicating my life to showing people things they can do to become more creative and how to leave an unforgettable mark in whatever it is they do.”

Orit Wolf in duet with opera singer Assaf Kacholi. Photo: courtesy

When the university discontinued her award-winning course for budgetary reasons, she was jolted out of one of her own paradigms – the false sense of job security – and turned her disappointment into an opportunity to do concert lectures.

“I started in a small Jaffa museum with 60 subscribers in 2006. Now I have over 4,000 annual subscribers for eight series I perform at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Haifa Auditorium, Rehovot, Ashdod and Ra’anana,” says Wolf, who encourages audiences to record, photograph, share and tweet her performance as long as their phones are in silent mode.

She also has a new series for English-speakers, Music and Muse, at Weil Auditorium in Kfar Shmaryahu.

Wolf confides that on occasion she takes her seven- and nine-year-old children to her concerts instead of school.

“The idea of obeying rules all the time, I think, is wrong. Breaking rules sometimes helps people think more clearly and changes how they look at things.”

For more information, click here.